Historically speaking the grotesque is a decorative wall painting of interwoven hybrid human or animal bodies, and mythical characters entwined with floral patterns, using curving spiraling foliage elements.

The name is derived from the "grotto" in Italian meaning "cave". Can be found in interiors of rooms or corridors or ‘hidden places’. The strange motifs of hybrids of plant, animal, and human forms were first discovered in the 15th century in Nero’s Golden Palace, the Domus Aurea.

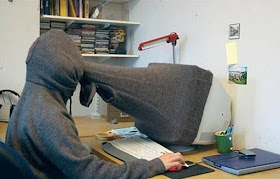

There is a place for humour, folly and satire in this kind of work that easily translates into contemporary versions.

These whimsical arrangements and motifs inspired work of the masters during the Renaissance, the Baroque, and the Rococo. Even postmodern artists working today.

Could it be that they retain a good working combination that opens up relevant debate between disparate elements, such as aesthetic beauty in the decorative vs the abject? Or the free-form mythical figures fusing bodies of humans and animals and plants within curved structures vs the crazed feeling from these exaggerated forms? Or the sheer enchanting absurdity of the characters mingling they way across the planes of the walls?

An alternate name for the original decorative grotesques in sisteenth-century Italy was sogni dei pittori. The unsettled, fantastic world of dreams would indeed seem to provide the perfect setting for the emergence of the grotesque, as they often do in actual experience, notably in nightmares. The surrealists often exploit the grotesque in attempting to mirror the dream-world of the subconscious, as can be seen in many of Dalí´s masterpieces. Much earlier did Albrecht Dürer realize that the grotesque and the world of dreams are very closely related: "If a person wants to create Traumwerk (el trabajo del sueño que da lugar a la fantasía, the stuff the dreams are made of), let him freely mix all sorts of creatures."

This is not to imply, of course, that artists created dreamworks in anything approaching a dream-state, nor does it imply that the verisimilar reproduction of a dream-state was uppermost in their minds when resorting to the grotesque prolifically; rather, that its use as a frame gave them the sort of "poetic license" requisite for indulging in fantasy, an extra justification for the creation of the grotesque in abundance. Artists thus embraced consciously the fantasy-liberating nature of dreams.

Crearon así un mondo che non esiste se non nella fantasia dei poeti, nei sogni dei pittori, nella magia degli artisti.

FORZA ITALIA! - "Se il vigore va bene... avanti con il pene. Ma, se la situazzione e dificile e la forza mingua... avanti con la lingua. Se questa posizione si torna imposibile e tutto intento inhumano... avanti con la mano. Ma, se niente funziona... e tutto é nullo... avanti con il culo. Ma, Avanti... Sempre Avanti! Che questo è lo importante" (Giussepe Kilome Il Cabrone).

The original use of the term grotesque in the Italian Renaissance--to designate an ornamental style disregarding the laws of statics, symmetry, and proportion and mixing animate and inanimate forms suggested not only something playfully gay and carelessly fantastic, but also something ominous and sinister. From the start, such dissolution of reality into monstrosities was associated with "the dreams of painters" (sogni dei pittori); but grotesque was often confused with the two-dimensional moresque and perspectival, tectonic arabesque as a stylistic term, and by the later seventeenth century it was further extended figuratively to signify any appearance, manner, or behavior which was extravagant, bizarre, capricious, silly, ridiculous, hence comic in a shallow and general sense. The first noteworthy transfer of the term from art to literature in the Mannerist and Baroque period appears in Montaigne´s description of his own Essais as "crotesques et corps monstrueux, rappiecez de divers membres, sans certaine figure, n'ayants ordre, ny proportion que fortuite". The antithetical, contradictory qualities of being inhere in the doubled, self-reflective consciousnes of Montaigene: "Je n'ai vu monstre ey miracle au monde, plus esprès que moi-même".

De Bosch a los surrealistas, pasando por Brueghel, Hogarth y Goya, lo que los italianos llamaban i sogni dei pittori, es decir, lo grotesco, nos ofrece la posibilidad de distraernos de nuestra inquietud interior al combatirla con un sentimiento más poderoso: el horror angustiado que nos causa el espectáculo de un mundo al revés, en que la naturaleza se revuelve monstruosamente contra sí misma y no obedece ya a sus propias leyes, en que la diferencia entre personas y objetos parece borrarse, en que lo inesperado nos aguarda en cada esquina. Como el manierismo, lo grotesco es anticlásico; pero a diferencia del manierismo, no es el yo el que se siente enfermo, sino el mundo externo todo el que parece haberse vuelto loco. El insondable caos externo borra o disimula toda angustia subjetiva, sumiéndola en otra más vasta e impersonal. Un mundo enajenado en que los objetos adquieren vida propia y en que lo humano ha sido herido y distorsionado tan gravemente que cesa propiamente de ser humano, nos ofrece, además el consuelo de que podemos rechazarlo de golpe, íntegramente, mediante una carcajada (Manuel Durán, Quevedo contra Quevedo, Palibrio, 2013, pp. 155-156).

The name is derived from the "grotto" in Italian meaning "cave". Can be found in interiors of rooms or corridors or ‘hidden places’. The strange motifs of hybrids of plant, animal, and human forms were first discovered in the 15th century in Nero’s Golden Palace, the Domus Aurea.

There is a place for humour, folly and satire in this kind of work that easily translates into contemporary versions.

These whimsical arrangements and motifs inspired work of the masters during the Renaissance, the Baroque, and the Rococo. Even postmodern artists working today.

Could it be that they retain a good working combination that opens up relevant debate between disparate elements, such as aesthetic beauty in the decorative vs the abject? Or the free-form mythical figures fusing bodies of humans and animals and plants within curved structures vs the crazed feeling from these exaggerated forms? Or the sheer enchanting absurdity of the characters mingling they way across the planes of the walls?

An alternate name for the original decorative grotesques in sisteenth-century Italy was sogni dei pittori. The unsettled, fantastic world of dreams would indeed seem to provide the perfect setting for the emergence of the grotesque, as they often do in actual experience, notably in nightmares. The surrealists often exploit the grotesque in attempting to mirror the dream-world of the subconscious, as can be seen in many of Dalí´s masterpieces. Much earlier did Albrecht Dürer realize that the grotesque and the world of dreams are very closely related: "If a person wants to create Traumwerk (el trabajo del sueño que da lugar a la fantasía, the stuff the dreams are made of), let him freely mix all sorts of creatures."

This is not to imply, of course, that artists created dreamworks in anything approaching a dream-state, nor does it imply that the verisimilar reproduction of a dream-state was uppermost in their minds when resorting to the grotesque prolifically; rather, that its use as a frame gave them the sort of "poetic license" requisite for indulging in fantasy, an extra justification for the creation of the grotesque in abundance. Artists thus embraced consciously the fantasy-liberating nature of dreams.

Crearon así un mondo che non esiste se non nella fantasia dei poeti, nei sogni dei pittori, nella magia degli artisti.

FORZA ITALIA! - "Se il vigore va bene... avanti con il pene. Ma, se la situazzione e dificile e la forza mingua... avanti con la lingua. Se questa posizione si torna imposibile e tutto intento inhumano... avanti con la mano. Ma, se niente funziona... e tutto é nullo... avanti con il culo. Ma, Avanti... Sempre Avanti! Che questo è lo importante" (Giussepe Kilome Il Cabrone).

|

| Grotteschi |

The original use of the term grotesque in the Italian Renaissance--to designate an ornamental style disregarding the laws of statics, symmetry, and proportion and mixing animate and inanimate forms suggested not only something playfully gay and carelessly fantastic, but also something ominous and sinister. From the start, such dissolution of reality into monstrosities was associated with "the dreams of painters" (sogni dei pittori); but grotesque was often confused with the two-dimensional moresque and perspectival, tectonic arabesque as a stylistic term, and by the later seventeenth century it was further extended figuratively to signify any appearance, manner, or behavior which was extravagant, bizarre, capricious, silly, ridiculous, hence comic in a shallow and general sense. The first noteworthy transfer of the term from art to literature in the Mannerist and Baroque period appears in Montaigne´s description of his own Essais as "crotesques et corps monstrueux, rappiecez de divers membres, sans certaine figure, n'ayants ordre, ny proportion que fortuite". The antithetical, contradictory qualities of being inhere in the doubled, self-reflective consciousnes of Montaigene: "Je n'ai vu monstre ey miracle au monde, plus esprès que moi-même".

|

| La grottesca |

De Bosch a los surrealistas, pasando por Brueghel, Hogarth y Goya, lo que los italianos llamaban i sogni dei pittori, es decir, lo grotesco, nos ofrece la posibilidad de distraernos de nuestra inquietud interior al combatirla con un sentimiento más poderoso: el horror angustiado que nos causa el espectáculo de un mundo al revés, en que la naturaleza se revuelve monstruosamente contra sí misma y no obedece ya a sus propias leyes, en que la diferencia entre personas y objetos parece borrarse, en que lo inesperado nos aguarda en cada esquina. Como el manierismo, lo grotesco es anticlásico; pero a diferencia del manierismo, no es el yo el que se siente enfermo, sino el mundo externo todo el que parece haberse vuelto loco. El insondable caos externo borra o disimula toda angustia subjetiva, sumiéndola en otra más vasta e impersonal. Un mundo enajenado en que los objetos adquieren vida propia y en que lo humano ha sido herido y distorsionado tan gravemente que cesa propiamente de ser humano, nos ofrece, además el consuelo de que podemos rechazarlo de golpe, íntegramente, mediante una carcajada (Manuel Durán, Quevedo contra Quevedo, Palibrio, 2013, pp. 155-156).

Resources

Domus Aurea

Estilo fantasía de la antigua Roma

Raphael: The Vatican Loggia

Mariano Akerman