John Ruskin advances his theory of the grotesque in

Modern Painters and

The Stones of Venice, which is an immense three volume work wherein he talks about the history of Venetian art and architecture; sometimes generally, sometimes literally stone by stone.

In the second volume of

Stones, Ruskin argues that "grotesqueness" is one of the fundamental ingredients of Gothic architecture, along with savageness, changefulness, naturalism, rigidity and redundance. On this grotesque quality he comments that: "every reader familiar with Gothic architecture must understand what I mean, and will, I believe, have no hesitation in admitting that the tendency to delight in fantastic and ludicrous, as well as in sublime, images, is a universal instinct of the Gothic imagination" (LXXII).

In the third volume of

Stones, Ruskin discusses the grotesque "corruption" of the Renaissance style, which is understood by Ruskin to reflect a wider corruption of Christian values and the loosening of religion's hold upon the minds and souls of the citizens of Venice (

Groteskology: Ruskin I).

Ruskin argues that the "corruption" of Venice's beautiful Gothic architecture, during what he calls the "grotesque renaissance," accords with a more general collapse of social values that is reflected in the worst kind of grotesque [

his example].[+] Having already commented on the grotesque as an essential quality of Gothic, he now comes to exploring the difference between the new, heinous grotesquerie and the earlier, more positive kind: "It must be our immediate task, and it will be a most interesting one, to distinguish between this base grotesqueness, and that magnificent condition of fantastic imagination, which was above noticed as one of the chief elements of the Northern Gothic mind" (III, XVI).

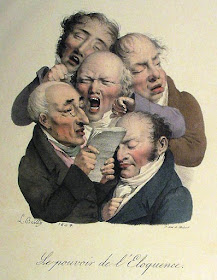

Ruskin detects two components in the grotesque: "It seems to me that the grotesque is, in almost all cases, composed of two elements, one ludicrous, the other fearful; that, as one or other of these elements prevails, the grotesque falls into two branches, sportive grotesque and terrible grotesque; but that we cannot legitimately consider it under these two aspects, because there are hardly any examples which do not in some degree combine both elements; there are few grotesques so utterly playful as to be overcast with no shade of fearfulness, and few so fearful as absolutely to exclude all ideas of jest. But although we cannot separate the grotesque itself into two branches, we may easily examine separately the two conditions of mind which it seems to combine; and consider successively what are the kinds of jest, and what the kinds of fearfulness, which may be legitimately expressed in the various walks of art, and how their expressions actually occur in the Gothic and Renaissance schools" (III, XXIII).

Numerous contemporary discussions maintain the validity of this structure in which the grotesque finds expression as a combination of the comic and the fearful. According to Ruskin, "the mind, under certain phases of excitement, plays with terror" (XLV). The grotesque is thus understood as that which enables terrible things to be set out in the open, to be played with in a form of personal and cultural exorcism.

Ruskin discussed this earlier, in the

fourth volume of

Modern Painters, where he commented that: "A fine grotesque is the expression, in a moment, by a series of symbols thrown together in bold and fearless connection, of truths which it would have taken a long time to express in any verbal way, and of which the connection is left for the beholder to work out for himself; the gaps, left or over-leaped by the haste of the imagination, forming the grotesque character" (97-98).

Groteskology: Ruskin II; [+] Maschera in pietra sulla porta del campanile in Campo Santa Maria Formosa. John Ruskin la definisce, ne "Le pietre di Venezia", "una testa --colossale, bestiale, mostruosa-- ammiccante in una degradante volgarità, troppo brutta per essere descritta o per essere guardata più che per un attimo."

Collection database:

The British Museum, London

A Cruel Caricature? This particular vase is a type of pottery called Knidian Relief Ware, which was manufactured in large quantities in and around Cnidus in south-east Turkey. In Knidian Relief Ware grotesque heads were a very popular motif, along with animals such as rams, lions and dogs. Cruelly caricatured representations of people were a very popular motif in pottery vases, as indeed they were in other areas of art, for example sculpture and terracottas. Bibl. J.W. Hayes,

Handbook of Mediterranean Roma, London: British Museum, 1997; S. Walker,

Roman Art, London, 1991; P. Roberts, "Mass-production of Roman Fine Wares" in

Pottery in the Making: World-5, London: British Museum, 1997, pp. 188-93 (

British Museum).

Dragón en el románico aragonés

Basilisco

Este reptil fabuloso, cuyo nombre significa precisamente “reyezuelo” (βασιλίσκος basilískos: «pequeño rey») es sin lugar a dudas el rey del Fisiólogo, un animal que pertenece por entero a la esfera de la imaginación o al acervo simbólico y al que jamás se le ha encontrado su análogo en la fauna animal.

Su aparición en la mayoría de los bestiarios es una referencia obligada; casi todos los textos aluden a esta criatura describiéndola como un animal de pequeño porte, pero “tan ponzoñoso, que mata a los hombres con su sola mirada. Son reyes -basileus- de las serpientes; y no hay en el mundo bestia, grande o pequeña, que se les quiera enfrentar. Y allá por donde pasan, debido al gran veneno que tienen, secan los árboles y las hierbas. Y todos los años mudan la piel, como hace la serpiente, y después las renuevan.

La imagen del basilisco evoluciona a lo largo del tiempo, aunque permanecen algunos elementos en su descripción general, como el parentesco con las serpientes y lo mortífero de su mirada: ” En el siglo VIII, el basilisco era considerado una serpiente con unos cuernos en la cabeza y una mancha blanca en la frente en forma de corona. (…) Más tarde, en el medievo, pasa a ser un gallo con cuatro patas, plumas amarillas, grandes alas espinosas y cola de serpiente, que podía terminar en garfio, cabeza de serpiente o en otra cabeza de gallo. Hay versiones de esta criatura mitológica con ocho patas y escamas en vez de plumas. Plinio el Viejo lo describe como una culebrilla de escaso tamaño y pésimo genio ya que "su potente veneno hace marchitarse las plantas y su mirada es tan virulenta que mata a los hombres."

En otras fuentes las descripciones lo hacen semejante al gallo, con el que comparte su cresta, tamaño y porte: “Se figura como un gallo con cola de dragón o una serpiente con alas de gallo.” Todo su simbolismo deriva de esta asociación con el gallo y la serpiente: “El basilisco representaría el poder real que fulmina a quienes le faltan al respeto; a la mujer casquivana que corrompe a quienes de antemano no la reconocen y no pueden en consecuencia evitarla; los peligros mortales de la existencia, que uno no advierte a tiempo, y frente a los cuales son los ángeles divinos la única salvaguarda”. Esta asociación simbólica del basilisco con la mujer, de clara ascendencia judeocristiana, procede de la misma fuente que vincula a Eva con la Serpiente, y es más frecuente en el Renacimiento; así “durante el siglo de Oro, la literatura española aparece salpicada de referencias a la bestia, normalmente para compararla a la mirada de la amada. Lope de Vega, Quevedo o Cervantes usan a la criatura en sus textos.)

A propósito de esta extraña criatura dice el Bestiario de Brunetto que “cuando avanza, la mitad anterior de su cuerpo se yegue verticalmente, la otra mitad queda como en las demás serpientes, enroscada. Y por muy feroz que sea el basilisco, lo matan las comadrejas (…) Y sabed que Alejandro (Magno) los vio; mandó hacer entonces unas grandes ampollas de vidrio, en las que entraban hombres que podían ver a los basiliscos, mientras que éstos no los veían, y los mataban con sus flechas; y mediante tal añagaza, libro de ellos a sí mismo y a su ejército.”

E Isidoro en sus Etimologías: «Basilisco es nombre griego; en latín se interpreta regulo, porque es la reina de las serpientes, de tal manera que todas le huyen, porque las mata con su aliento y al hombre con su vista; más aún, ningún ave que vuele en su presencia pasa ilesa, sino que, aunque esté muy lejos, cae muerta y es devorada por él. Sin embargo le vence la comadreja, que los hombres lanzan a las cavernas en las que se esconde el basilisco. Cuando éste la ve huye y es perseguido hasta que es muerto por ella. Nada dejó el Padre de todas las cosas sin remedio. Su tamaño es de medio pie y tiene líneas formadas por puntas blancas. Los régulos, como los escorpiones, andan por lugares áridos, pero cuando llegan a las aguas se hacen acuáticos. Sibilus es el mismo basilisco, y se le da este nombre porque con sus silbidos mata antes que muerde.»

Más curiosas son las explicaciones que sobre el origen de este enigmático monstruo nos brindan los diferentes bestiarios conocidos, pues casi todos coinciden en afirmar que el basilisco “nace de un huevo de gallo viejo, de siete o catorce años, huevo redondo depositado en el estiércol y empollado por un sapo, una rana o una sierpe venenosa. “

Algunos autores ya en la antigüedad manifestaron sus dudas sobre estas peregrinas historias sobre el origen de la mítica bestia: “que nazca de un huevo puesto por n gallo viejo, es difícilmente creíble; no obstante, algunos afirman con gran confianza que, cuando el gallo se vuelve viejo y cesa de montar a sus gallinas, nace en su interior, de su simiente corrompida, un huevecillo cubierto con una delgada película en vez de cáscara; incubado por un sapo alguna criatura semejante, el huevo produce el gusano venenoso, aunque no este basilisco, este rey de las serpientes. ”

Advierten las leyendas que es extremadamente difícil capturar vivo un basilisco. El único medio, como en el caso de otras criaturas que matan con sólo mirar, es un espejo: “en él la mirada terrible de letal potencia, reflejada y vuelta sobre el basilisco mismo, lo mata; o bien los vapores ponzoñosos que lanza le procuran la muerte que él quiso dar.” En este episodio es evidente la relación con la Gorgona, cuya visión causaba la muerte petrificando al individuo; del mismo modo que la representación de la cabeza de la Medusa en el escudo de Atenea era capaz de destruir a los enemigos de la diosa: “Lucano refiere que de la sangre de Medusa nacieron todas las serpientes de Libia: el Áspid, la Anfisbena, el Amódite, el propio Basilisco; el pasaje está en el libro noveno de la Farsalia”.

El salmista equipara al basilisco con el áspid, poniéndolos en relación con el dragón y otros símbolos del Adversario: “Los ángeles te llevarán en palmas, para que tu pie no tropiece en la piedra, pisarás el áspid y el basilico; hollarás el léon y el dragón (Sal. XC, 12-13) “

En el ámbito alquímico también prolifera la imagen del basilisco, simbolizando el poder devastador y regenerador del fuego, en un simbolismo cercano al de la salamandra. La aparición del basilisco preludia en cierto sentido el inicio de la transmutación de los metales. En algunos tratados antiguos de medicina tradicional el basilisco se usa –como se usaba antaño el polvo de cuerno de rinoceronte– como remedio medicinal, mezclado con otros ingredientes que resultarán en ungüento o pócima de milagrosos efectos.

La representación del basilisco nos sugiere, al margen de la carga moralizante que le prestaron los autores de los bestiarios, asociaciones con el dios Abraxas de los gnósticos, a menudo representado con cabeza de gallo y cuerpo de serpiente, y nos trae a la memoria el recuerdo de algunas criaturas fantásticas de la ciencia ficción moderna, verbigracia aquel octavo pasajero vermiforme y ponzoñoso que, como el basilisco, gozaba de idéntico mal genio.

http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilisco_(criatura_mitol%C3%B3gica)

http://marinni.livejournal.com/498964.html

http://www.jungba.com.ar/editorial/body_texto_editorial27.asp

http://www.viajesconmitia.com/2011/02/07/el-basilisco-rey-del-fisiologo/

http://www.revistamirabilia.com/

John Mandeville, Libro de las maravillas del mundo, 1540

Como grandes apasionados de los viajes y las mirabilia naturae, no podíamos faltar a esta cita ineludible con el aventurero y expedicionario de leyenda Juan de Mandávila, y su obra, conocida como Libro de las Maravillas:

“Nos encontramos ante uno de los libros de viajes más emblemáticos y populares del género en su modalidad de “viaje imaginario” (…) Junto con el Libro de las maravillas de Marco Polo (…) es sin duda, el de mayor difusión en la Europa medieval, desde su aparición en la segunda mitad del siglo XIV hasta el periodo renacentista . (…) Sin embargo, cabe preguntarse por qué la materia de viajes - en sus distintas manifestaciones- adquiere una presencia autónoma y constante a lo largo de la Edad Media y la sigue manteniendo durante muchas décadas después, independientemente de las nuevas variantes del género (largas navegaciones, naufragios, diarios de a bordo, etc.) que responden a las nuevas exigencias de “aventura” y entretenimiento en los siglos XVI y XVII”

“El viaje de Mandeville (…) combina la forma de peregrinación, con la adición de dos tipos de materia fabulosa: las varias leyendas devotas asociadas con iertos lugares de la Tierra Santa y buena cantidad de monstruos“ en la tradición de la Naturalis Historia de Plinio el Viejo– “ todo eso enmarcado en la presentación del viaje como aventura caballeresca relatada a posteriori, es decir, desde el recuerdo de los peligros y las hazañas del pasado que el Mandeville anciano revive desde el presente.”

“El hombre medieval, en su condición de homo viator, va a intentar aprehender estos otros mundos -tradicionalmente susceptibles de todo tipo de especulaciones y mitologías- como parte insólita de la realidad conocida(…)Viajero y también erudito parece ser Mandeville - o, como mínimo parece pretenderlo- al combinar en su relato la elaboración más genuinamente novelesca tan característica de los libros de viajes con el tratamiento más descriptivo y teórico de la noticia geográfica”

Textos tomados de Juan de Mandávila, Libro de las maravillas del mundo, Valencia, 1540; edición realizada por Estela Pérez Bosch

http://valdeperrillos.com/book/export/html/3272

Teratologia

http://valdeperrillos.com/books/pasos-perdidos/teratologia-renacentista

http://www.flickr.com/photos/renzodionigi/tags/%E2%80%9Cmonstrous/

Conjoined twins

http://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/conjoined/index.html

Ambroise Paré (1510-90),

Oeuvres, 1585

http://www.viajesconmitia.com/2010/03/28/los-monstruos-y-prodigios-de-ambroise-pare/

NLM http://archive.nlm.nih.gov/proj/ttp/paregallery.htm

Conrad Gessner, Historiae Animalium, 1551

http://archive.nlm.nih.gov/proj/ttp/Gesnergallery.htm

Olaus Magnus, Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus, 1555

Conrad Lycosthenes (Conradus Lycosthenes, Corrado Licostene),

Prodigiorum ac ostentorum chronicon, 1557; engravings by Theodor de Bry (1528-1598). Obra renacentista. El término “crónica” corresponde con exactitud con el espíritu y el contenido de las obras, y sus descripciones maravillosas y fantásticas de los fenómenos y prodigios procedentes de la cultura medieval. Compuesta por magníficas xilografías de Theodor de Bry (1528-1598) en las que se representan aves con malformaciones teratológicas, que eran vistas a menudo como presagios de infortunio o desgracias, o anunciadores de calamidades y catástrofes cercanas.

http://www.propheties.it/nostradamus/prodigiorum/prodigiorum1.html

http://www.summagallicana.it/Licostene%20Lycosthenes%20Conrad%20Wolffhart/Licostene.htm

Fortunio Liceti,

De Monstrorum natura, caussis et differentiis (On the nature, causes and differences of monsters), 1616. Fortunio Liceti, absoluto seguidor de Aristóteles, en su De Perfecta Constitutione hominis in utero, fundamentará sus argumentos en la irreflenable fuerza y capacidad generativa de la Naturaleza que no teme a obstáculos o límites en su infinita variedad de expresión, viendo aquí la razón primera de la presencia de monstruos en la Creación. En 1616 Licetti publicaría su De Monstrorum Natura, obra seminal que marcaría el inicio de los estudios de las malformaciones teratológicas del embrión. En ella describe numerosos monstruos, reales e imaginarios, y busca las razones para explicar su extraña apariencia. Su aproximación al tema difiere de la perspectiva al uso entre los expertos europeos de la época, puesto que veía a los monstruos no como un castigo divino sino como el producto de una anomalía o rareza natural. Asímismo sostendría la idea de la transmisión de caracteres similares de padres a hijos, presagiando los estudios de genética.

La obra de Liceti parte de una definición del “monstruo” que retoma el significado etimológico original: con el término monstrum se indica todo aquello que suscita admiración, sorpresa y maravilla -res mirabilis- sea en modo positivo o negativo –véase el horror sagrado–. El monstruo, asociado a la capacidad de asombro y maravilla, fuente y principio de toda búsqueda en pos de la sabiduría, vuelve a retomar su antigua función de custodio y guardián del tesoro, que en este caso simboliza la gnosis, el verdadero conocimiento.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fortunio_Liceti

http://www.taringa.net/posts/imagenes/1829245/Monstruos-imaginarios-antiguos_-Excelentes_.html

http://marinni.livejournal.com/417783.html

http://www.linguaggioglobale.com/mostri/txt/31.htm

http://www.viajesconmitia.com/2011/03/13/los-monstruos-de-liceti/

Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522-1605),

Monstrorum Historia, 1642. A los “monstruos marginales del arte y la literatura, a los prodigios y maravillas, a su mundo y a sus paisajes” (1) está consagrada esta entrada sobre la Monstrorum historia de Ulisse Aldrovandi (1662), una obra antigua que no deja de maravillarnos por su temática, que aborda todo tipo de aberraciones y deformaciones naturales, anatomía mórbida, monstruos y criaturas extraordinarias, naturales o mitológicas. Escrita originalemente en latín, el texto se ilustraba profusamente con innúmeras imágenes sumamente descriptivas, que aún hoy poseen una gran fuerza visual.

http://www.filosofia.unibo.it/aldrovandi/pinakesweb/compdetail.asp?Pag=1&compid=3431

http://www.filosofia.unibo.it/aldrovandi/pinakesweb/compdetail.asp?Pag=6&compid=3431

http://www.filosofia.unibo.it/aldrovandi/

http://www.filosofia.unibo.it/aldrovandi/pinakesweb/main.asp?language=it

http://num-scd-ulp.u-strasbg.fr:8080/189/

http://www.viajesconmitia.com/2010/03/03/monstrorum-historia/

Cabinet of Curiosities

http://www.mundieart.com/cabinet/museums.htm

|

C.J. Grant, "Singular Effects of the Universal Vegetable Pills on a Green Grocer," lithograph, London 1831. A man in bed with vegetables sprouting from all parts of his body; as a result of taking J. Morison's vegetable pills. Wellcome Images, London

Ref. alternative medicine |

José Guadalupe Posada

http://www.viajesconmitia.com/2010/04/23/%C2%A1viva-la-muerte/

Human Marvels

Pueden llamarles monstruos, fenómenos, prodigios, aberraciones, engendros del infierno -como ustedes quieran- pero yo los llamaré increibles y maravillosos seres humanos, en esta crónica de sus inspiradoras historias del triunfo del espíritu y la voluntad sobre la naturaleza, el destino y el juicio del hombre.

Así se presenta al mundo el artífice de The Human Marvels, donde nos presentan a esta “gente peculiar”. Disfruten del espectáculo trágico de la vida humana. De esta fabulosa y altamente recomendable página hemos sacado algunas de las fotografías que les ofrecemos, con ánimo esclarecedor, for your enlightenment.

http://thehumanmarvels.com/

http://www.phreeque.com/

http://www.viajesconmitia.com/2010/03/29/la-feria-de-las-vanidades/

Freaks, dir. Tod Browning, USA, 1932. La palabra “Freak” equivalía, en los primeros años del siglo XX, a la expresión “monstruo de feria”, pues hacía referencia concretamente a engendros, prodigios o fenómenos de la naturaleza, “a personas -que no monstruos- diferentes, que por azares y caprichos de la biología, nacieron o crecieron con taras, deformidades o configuraciones especiales. Gente que ” también formaba parte de la sociedad y que llegaron a mover millones de dólares como atracción de feria en la época de la Gran Depresión Americana y fue a partir de ahí cuando los diccionarios en inglés empezaron a recogerla.”

“La película de 1932 de Tod Browning Freaks (La Parada de los Monstruos) refleja esa realidad, en la que un grupo de actores circenses va de ciudad en ciudad mostrando a un público deseoso por ver algo diferente con un éxito arrollador y delicioso; sin embargo, casi un siglo después, La Parada de los Otros Monstruos, claramente la nuestra, en la que los abominables seres anormales somos nosotros, aún no está preparada e incluso discrimina lo diferente, lo que está fuera del mainstream; exactamente igual que Browning lo recogió en película hace ya casi un siglo.”

No podemos hacernos una ligera idea del profundo impacto que la película Freaks, de 1932, tuvo en la audiencia de su época. Incluso hoy día un espectador medio puede sufrir un ligero shock ante la potencia primigenia de este film y los terroríficos pero tiernos monstruos de feria, los actores reales de circo que actúan en él. Han tenido que transcurrir varios lustros hasta que esta cinta lograra su actual estatus de película de culto, porque hasta no hace mucho estuvo prohibida por la crudeza de la historia y sobre todo por sus imágenes. Lo más curioso es precisamente que todos los actores que interpretaron un papel en Freaks eran personas con deformidades reales y casi no se usaron efectos especiales ni de maquillaje. El director, Browning, escogió cuidadosamente en el casting a los “freaks”(fenomenos) protagonistas de su cinta, antes que usar disfraces o artificios de ningún tipo, para dar más verismo y credibilidad a la narración.

“Vista hoy en día, la película resulta [...] rodada con sencillez [...], Browning plantea un cuento de terror moral en una atmósfera extraña pero en todo momento realista. Tal y como sucedió en el mismo rodaje, los freaks del film parecen tener un comportamiento mucho más noble que el de la sociedad que les rodea y les aparta por el simple hecho de haber sufrido alguna deformidad.

http://www.cinetelia.com/friquis-otra-parada-monstruos.html

http://www.miradas.net/0204/clasicos/2003/0312_freaks.html

http://www.viajesconmitia.com/2010/03/29/la-parada-de-los-monstruos/

Jean-Paul Sartre, Preface to Frantz Fanon’s

Wretched of the Earth, (Les damnés de la terre ), 1961: "There is nothing more consistent than a racist humanism, since the European has only been able to become a man through creating slaves and monsters" (

source).

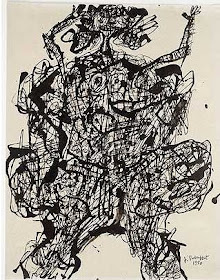

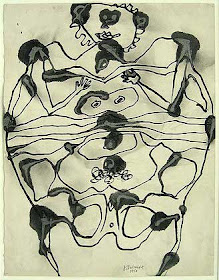

François Houtin, Jardins, c. 1983-2000. Sorprendente maestro del grutesco y el arabesco, adepto del asunto simbólico del Árbol de la vida y sus múltiples ramificaciones iconográficas, desde el laberinto vegetal al hortus conclusus, pasando por el capriccio ornamental ampliamente inspirado en ramas, vástagos, raíces y formas arborescentes y orgánicas. Su dibujo abigarrado y barroco, en un sobrio blanco y negro y dominado por el rigor de la línea grabada o burilada, es capaz sin embargo de evocar los más singulares y remotos lugares de la imaginación. El jardín soñado es el tema central de la obra de este grabador francés, François Houtin (1950- ), a cuya descripción detallada [h]a dedicado buena parte de su trayectoria artística, con singular fortuna. Su infancia en el entorno de Craon, cerca de Mayenne, en la región rural de Anjou, propiciaría su acercamiento al tema del paisaje y el jardín imaginario. El propio Houtin trabajaría un tiempo como jardinero y florista, mientras completaba su formación de arquitecto y paisajista, dos disciplinas cuya influencia se intuye en su monumental e inspirador trabajo, entre las visiones de Piranesi y la atmósfera apasionada y misteriosa del paisaje romántico (

Flegetanis;

Galleria del Leone;

Marinni).

|

Thomas Mangold

„Aus einer Mücke eine Elefanten machen”

To make an elephant out of a mosquito, 2010

photograph and computer graphic design

Artist's remark: "If you rearrange reality and/or approach it in a new and unfamiliar angle there are endless possibilities to create stunning stuff." |

Ian McCormick,

Encyclopedia of the Marvelous, the Monstrous, and the Grotesque, including

illustrations list, London, 2000

Jahsonic 2006-9

Gargoyle

Natural History

Ugly

Awe of nature, taste for the bizarre, thirst for knowledge

Monsters are not signs of God’s punishment

Tumors and other major deformities in medical illustration

Surrealism avant la lettre

GROTESCOLOGY

Ancient hybrids

Graeco-Roman figurines

Franco-Spanish grotesques

Andrea Riccio

Castillo Pedro Fajardo

Arent van Bolten

Nicasius Roussel

Baroque heads

Ruskin pt1

Ruskin pt2

Double_Dichotomy

Patricia Piccinini

Lucy McRae

Eco_ads

Trampantojo

http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trampantojo

http://www.viajesconmitia.com/category/las-uvas-de-zeuxis/

William Hogarth: The Analysis of Beauty

Early Comics: TS Sullivant

http://www.old-coconino.com/sites_auteurs/sullivant/menu.htm

George Quaintance 1950s Covers