Joris Hoefnagel (1542–1601) was a South-Netherlandish painter and engraver. The son of a diamond merchant, he was born in Antwerp. He travelled abroad, making drawings from archaeological subjects. Hoefnagel was a pupil of Hans Bol at Mechlin. He was later patronized by the elector of Bavaria at Munich and by the Emperor Rudolph at Prague. He died at Vienna in 1601.

He is famous for his miniature work, especially on a missal in the imperial library at Vienna; he painted animals and plants to illustrate works on natural history; and his engravings (especially for Ortelius's

Theatrum orbis terrarum, 1570 and Braun's

Civitates orbis terrarum, 1572) give him an interesting place among early topographical draftsmen.

In 1561-62, Georg Bocskay, imperial secretary to the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I, inscribed the

Mira calligraphiae monumenta as a testament to his preeminence among scribes. He assembled a vast selection of contemporary and historical scripts, which nearly thirty years later were further embellished by Joris Hoefnagel, Europe's last great manuscript illuminator. The original manuscript is now in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, California.

Hoefnagel was commissioned by Rudolf II to illustrate

Mira calligraphiae monumenta (The Model Book of Calligraphy), which he began around 1590, more than 15 years after the death of the Croatian calligrapher, Georg Bocskay.[1] In the work, Hoefnagel's illuminations show the spread of interest in botany and zoology at the end of the sixteenth century. His imagery encompasses plants, flowers and fruits, insects and small animals, and even some imaginary beings too.

|

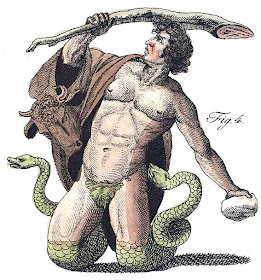

| A grotesque head, by Hoefnagel.[2] |

By mid-sixteenth century, the grotesque had established itself at Flanders, where, "in 1555, an artist called Cornelis Floris designed 18 sheets with human faces made up from vegetal elements, some highly stylized, others still recognizable as leaves and fruits," which were engraved by Frans Huys in Antwerp. [...] The grotesque came to be applied to all manner of decorative arts: ceramics, tapestry, embroidery, furniture-making, jewellery, and so on. Its later, more exaggerated variant found its way back into manuscript-decoration too, notably in the illuminated alphabet in Joris Hoefnagel's

Mira calligraphiæ monumenta.[3]

|

Mira Calligraphia Monumenta

Calligraphic Abecedarium: Letter Construction

Grotesque faces in debt to the imagery of Cornelis Floris

Facsimile images are courtesy of Giornale Nuovo |

"In the 1500s, as printing became the most common method of producing books, intellectuals increasingly valued the inventiveness of scribes and the aesthetic qualities of writing. From 1561 to 1562, Georg Bocskay, the Croatian-born court secretary to the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I, created this Model Book of Calligraphy in Vienna to demonstrate his technical mastery of the immense range of writing styles known to him.

About thirty years later, Emperor Rudolph II, Ferdinand's grandson, commissioned Joris Hoefnagel to illuminate Bocskay's model book. Hoefnagel added fruit, flowers, and insects to nearly every page, composing them so as to enhance the unity and balance of the page's design. It was one of the most unusual collaborations between scribe and painter in the history of manuscript illumination.

Because of Hoefnagel's interest in painting objects of nature, his detailed images complement Rudolph II's celebrated

Kunstkammer, a cabinet of curiosities that contained bones, shells, fossils, and other natural specimens. Hoefnagel's careful images of nature also influenced the development of Netherlandish still life painting.

In addition to his fruit and flower illuminations, Hoefnagel added to the Model Book a section on constructing the letters of the alphabet in upper- and lowercase."[4]

|

Mira Calligraphia Monumenta

Calligraphic Abecedarium: Letter Construction |

Notes

1. Lee Hendrix and Thea Vignau-Wilberg,

Nature Illuminated: Flora and Fauna from the Court of the Emperor Rudolf II, 1997

2. A Green Man is a sculpture, drawing, or other representation of a face surrounded by or made from leaves. Branches or vines may sprout from the nose, mouth, nostrils or other parts of the face and these shoots may bear flowers or fruit. Commonly used as a decorative architectural ornament, Green Men are frequently found on carvings in ecclesiastical and secular buildings.

3. Misteraitch,

Faces of the Grotesque,

Giornale Nuovo, UK and Sweden, 10.06.2006

4.

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, USA, accessed 21.03.2013